It was a Sunday morning. We were sitting in my Professor friends study. I was enjoying my coffee.

Professor lit his cigar and said “Dr Modak, I feel that today benefits of waste recycling are simply overrated. We should stop much of the kind of recycling we do and I mean it”

I was shocked to hear Professor’s views. I did not understand why he was so much critical about recycling. I decided to protest.

I said “Professor. Recycling has many benefits. Firstly, it conserves natural resources as extraction of virgin materials is reduced. Further, recycling diverts waste that is to be sent to incinerators and landfill. Landfills take up valuable space and emit methane, a potent greenhouse gas; and although incinerators are not as polluting as they once were, they still produce noxious emissions. Unless you segregate waste at source you cannot do effective recycling. So, segregation of waste at source and recycling must go hand in hand”

Professor smiled. He said. “You have not updated enough Dr Modak. What you are saying is a rhetoric and well said in the national and international seminars”

“In the western world, recycling was introduced through the kerbside programmes that asked people to put paper, glass and cans into separate bins. In India, we are asking this to happen at the household level following three bins approach as per the Municipal Waste (Management & Handling) Rules. But we both know that this is simply not happening. It is frustrating to see that the waste-picker mixes your carefully segregated bins into one big bin and dumps the mixed waste into the collection vehicle every day”

I couldn’t disagree. Most citizens have been complaining about this dichotomy and hence don’t feel like segregating waste at source.

Professor continued.

“The trend now is back again to the co-mingled or “single stream” collection. The switch towards single-stream collection is being driven by emergence of new separation technologies that can identify and sort the various materials with little or no human intervention”

I thought that good waste segregation and recycling was everybody’s moral responsibility.

Professor added “San Francisco, which changed from multi bin to single-stream collection a few years ago, now boasts a recycling rate of 69%—one of the highest in America. Systems like TiTech—more than 1,000 of which are now installed worldwide—are able to sort numerous types of paper, plastic or combinations thereof up to 98% accuracy. The Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) are now set up with business models between the private sector with the local bodies.”

It was hard for me to believe that the mindset of the local governments in the west was slowly moving towards single stream collection and in India we are pressing for three bin-based waste segregation and collection system!

Professor was reading out from a handout. It said that notable benefits of single stream recycling were increased recycling rates, lesser requirement of space to store collection containers and reduced costs of hauling as separate pickups for different recycling streams were avoided.

However, I had three major concerns – one about the safety of the waste-pickers when they segregate the “single streams” as these would be contaminated. Second was about the safety of “waste processors” who process the waste to extract materials or make secondary products. My third concern was about the quality and safety of the recycled products. The recycled products while boasting their “greenness” and “creating green jobs” did not assure the quality and safety and hence were putting the consumers at risk.

Professor heard me alright but summed up saying that battle was between quality, reality (that nobody wants to segregate) and the convenience. For India at this point in time, single stream collection seems the most practical solution. I pointed out however, that we do not currently have indigenous machinery that can do this “magic of separation”.

Well, I have asked PMO to put this as a priority item in the Make in India program, said Professor.

I thought that we need to educate the citizens on the consumption itself and guide them to make “green choices” i.e. avoiding use of products to the extent possible that use harmful chemicals and non-biodegradable materials in the first instance. This will ensure “circularity”. The production patterns should be influenced by responsible consumption. The manufacturers will need to extend their involvement beyond the factory gates and across the life cycle.

When I expressed my view on this dual responsibility, Professor said that under pressure from environmental groups, such as the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition, computer-makers have established rules to ensure that their products are recycled in a responsible way. Hewlett-Packard has been a leader in this and even operates its own recycling factories in California and Tennessee. Dell, which was once criticized for using prison labor to recycle its machines, now takes back its old computers for no charge. And Apple is executing plans to eliminate the use of toxic substances in its products.

Oddly, these very companies and other product makers in India are rather silent when it comes to the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). Reports by Toxic Link on EPR on E-waste show the double standards. The Government and Environmental NGOs need to “arm twist” these companies.

The solution therefore, according to economists, activists and many in the design community, is to get smarter about both the design and disposal of materials, and shift responsibility away from local governments and into the hands of manufacturers. Products as well as packaging need to be designed with recycling in mind. Waste generation should be considered as a design flaw. Remedying this problem may require a complete rethinking of industrial manufacturing. This may sound like wishful thinking. The key question is can we design the product to make recycling easier?

Professor had more to say.

“Dr Modak, it is also important to understand recycling everything is not good. Economics of recycling is volatile, complex and contextual subject, You cannot generalize”

He said that the secondary materials market of recyclables is hard to control and speculate. The waste supply (in both quantity and characteristics) is highly variable and unless you stock, you cannot ensure getting decent economic returns from recycling business. To top, in countries like India, you have to manage with the informal sector that is not easy. This situation discourages the investors to deploy smart technologies of separation and processing – especially on extraction.

Further, not all recycled materials are created equal. Each material has a unique value, determined by the rarity of the virgin resource and the price the recycled material fetches on the commodity market. The recycling process for each also requires a different amount of water and energy and comes with a unique (and sometimes hefty) carbon footprint. All of this suggests it makes more sense to recycle only select materials than others from an economic and environmental standpoint.

Professor made this important point and ended the conversation by passing a study made by Kinnaman and his colleagues of 2014 called Socially optimal recycling rate: Evidence from Japan.

In this paper, using Japan as his test case Kinnaman evaluates the cost of recycling each material and the energy and emissions involved in recycling. Benefits are also assessed including simply feeling good about doing something for environment. He and his colleagues come to a controversial conclusion that an optimal recycling rate in most countries would probably be around 10 percent of the used goods.

To get the most benefit with the least cost, Kinnaman argues that we should be recycling more of some goods and less — or even none — of others. The composition of 10% should contain primarily aluminum, other metals and some forms of paper, notably cardboard and other source[s] of fiber. He wrote in a follow-up piece that “Optimal recycling rates for these materials may be near 100% while optimal rates of recycling plastic and glass might be zero.” I would add to his list the electronic goods.

Although several disagreed with Kinnaman’s 10% conclusion, his point that we need to be selective about what we recycle —resonated well with environmentalists and waste management experts alike.

I thought Kinnaman had an important point to make. He was asking two basic questions about recycling: Is it good for the environment? And does it make economic sense? The answers need a good study. But again, you can ask – isn’t recycling a moral responsibility? Or aren’t these computations reflecting our short term thinking?

I wonder whether we have conducted such studies on recycling practices in India. I thought of asking Professor to float a research project in partnership with Kinnaman and his colleagues. Indeed we need to revisit recycling to know its worth!

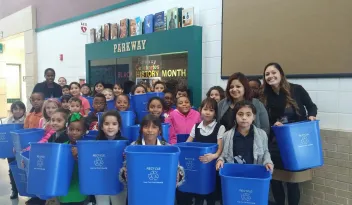

Cover image sourced from http://fortworthtexas.gov/kfwb/school-green-teams/